WordPress: Tracking Emerging Cryptomining Threats

This is a post written by James Yokobosky who works on the Defiant Threat Intelligence team. In his daily job he analyzes new WordPress threats as they emerge and adds detection capability to the Wordfence malware scanner. In addition to making sure we detect new malware, James also researches the pieces of malware we find to learn more about how they work, what they do and who is behind each campaign.

This post will give you an idea of what the workflow looks like for one of our Threat Analysts at Defiant, and will give you some insight into the emerging malware variants that we are seeing that target WordPress, how they work and what they do.

In this post, James describes his analysis of a Monero cryptocurrency miner that he recently examined, and explains how he tracked down and communicated with the command and control infrastructure for this malware variant. This post provides a clear illustration of how we rapidly add detection capability to the Wordfence malware scanner for emerging threats.

Fresh Malware Arrives for Analysis

![]() One of our sources of threat data at Defiant is cleaning hacked websites. In this case, Ivan, a member of our SST team had cleaned a hacked site and handed me the forensic data for analysis. The site had been hacked for months before the owner discovered that it had been compromised.

One of our sources of threat data at Defiant is cleaning hacked websites. In this case, Ivan, a member of our SST team had cleaned a hacked site and handed me the forensic data for analysis. The site had been hacked for months before the owner discovered that it had been compromised.

My normal routine is to start by verifying the files we already detect to check if there is any new information inside any of them. Usually there is not, and this infection did not yield any surprises in the files that Wordfence already detected.

What did surprise me is that the server had a large number of malicious files we have not seen before. The server had been infected for a long time, which may have left the attacker feeling confident enough to upload more valuable code. For us, a server with code we have not seen before is a treasure trove, because it immediately allows us to add new detection capability to the Wordfence malware scanner. If an attacker is caught in this situation, they generally have a bad day, because many of their files that may have previously been undetected by malware scanners will now be detected by our scan.

The first thing that made this attacker different from others is that, instead of using a standard javascript code obfuscator that just scrambles the code, they were using a finite wordlist to replace variable and function names in the code. When you look at the code, the variable and function names just seem like gibberish:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | function flu(sake,immobilitys) { chains = neatly / seehis; plotted = airs / lucky; storm = immediately + lowly; guests = soothed - lucie; } |

I immediately searched for other similar files out of the remaining samples and found several, then proceeded to write new signatures to detect those files. That accomplished, I moved on to the next file in the list. That was a basic PHP file that selectively redirects regular users, not search engines, to a malicious website. This is a standard thing we see, so I wrote a signature to detect this updated malware variant and moved on.

A Cryptomining Binary is Found

The third file was a bit more interesting. It was an ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, dynamically linked and stripped executable. It is a compiled file designed to run on a Linux system with a specific architecture, which has meaningful debugging data removed. It is similar to a Windows .exe file. These are relatively rare to see on WordPress infections because most web servers are not set up to allow arbitrary executables to run, and for this to work, an attacker needs to do more work on their end.

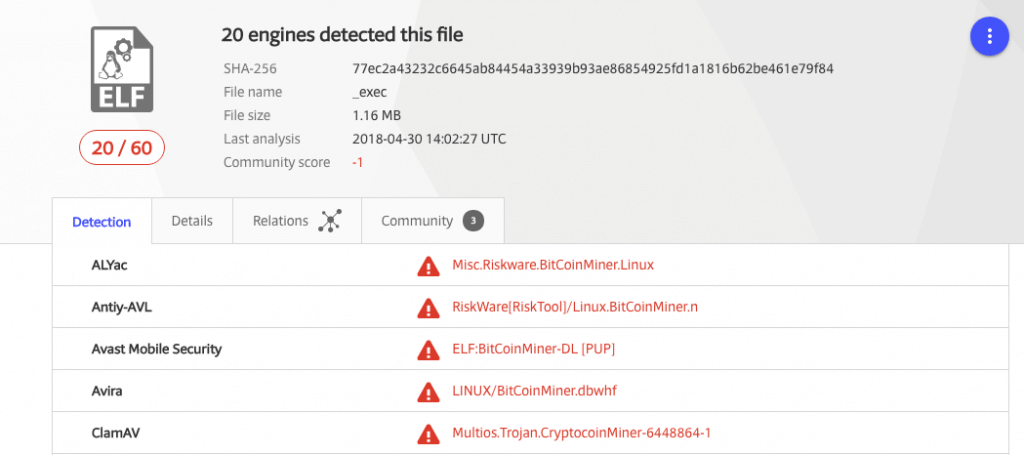

Because we already know this mystery file is doing something malicious, a good first step is to see if other antivirus software has already identified it. VirusTotal is an industry-standard way to achieve this, and sure enough a handful of the supported vendors do detect and identify the file.

The names VirusTotal returned provide a hint of what the file is:

- Misc.Riskware.BitCoinMiner.Linux,

- LINUX/BitCoinMiner.dbwhf,

- not-a-virus:HEUR:RiskTool.AndroidOS.Miner.b,

and similar suggest this is a cryptocurrency miner. At this point I performed a cursory inspection of the binary file to search for plaintext strings or recognizable disassembly and quickly identified the specific build: This is a mostly-stock xmrig ( https://github.com/xmrig/xmrig ) Monero-focused miner, well known in that community. Other artifacts inside the file allow me to confirm it was compiled on 2018-01-16 with a modern version of GCC.

I could tell there had been some modifications from the original source code. A quick look revealed that the change was hardcoding the addresses to send results – the pool addresses – so anyone running this specific file will be sending money to the attacker. At this point I had more than enough information to write a reliable signature to detect this malware, and I quickly did. We have more samples and I had yet to discover how the attacker runs and manages this hacked, zombie miner.

Analyzing the Configuration File

The next unique file shows another unusual level of technical sophistication from the “average” WordPress attacker: A separate configuration! Having just seen xmrig, it is easy to tell this JSON file contains instructions for how to run the mining executable.

It includes instructions to run in the background (hidden), use only 40% of the maximum available CPU, to slow down if the machine is otherwise busy, and other specific technical details related to the mining process. Luckily for us it is normally a terrible idea to run cryptominers on your WordPress web server if you are the person paying for it, so I can safely add a signature to identify this otherwise-benign configuration code without creating false positives.

Discovering the Command and Control Servers

With our next sample we hit the jackpot. It is a Python backdoor script that, while running, will check for new instructions against a centralized command and control server every 5 minutes. The backdoor itself is written to hide from system administrators. It masquerades as php-fpm ( https://php-fpm.org ) which is a normal process to be running on that server, and it is “well-behaved.” That is to say, it sits quietly and most of the time is not doing anything unusual or malicious.

Built into the backdoor is a report function, used to give the attacker data about the hacked machine and status updates on any activity, and a variety of normal system administration tasks related to downloading files, controlling processes, and executing commands. The code is well-formed and has obvious updates and adjustments made, implying the attacker has been developing and using this backdoor for some time. The method of hiding and the interval to check for new commands are easily configurable to evade intrusion detection systems and firewalls.

Most importantly, the command and control server’s IP address and method of communication is now available to us. I checked that it is still “up” – online and responding to requests – and put a pin in it. First I needed to develop a signature so that Wordfence detects this backdoor, then I inspected the remaining samples for more hints about the attacker before I risked exposing myself as infiltrating his botnet.

Only one of the remaining samples is noteworthy and related to the backdoor. It is a short Bash script used to start the backdoor running. Two things here again indicate a relatively sophisticated attacker: The backdoor is installed to look like a common part of a Linux shell and is executed in such a way that it looks like the legitimate owner of the server ran an innocuous command. This is easy to write a signature to detect, now that we have seen it. But this technique is an effective misdirect for a sysop trying to identify where the malicious activity is coming from. Had the attacker deleted this remnant file it would probably have been impossible to identify how the backdoor started, given the lack of forensic logging on the server.

Deploying Signatures to our Premium Customers

I confirmed that all of the previously undetected samples are detected by Wordfence with our new signatures and I immediately entered them into our Premium BETA feed. This allows us to receive instant feedback about possible bugs or false positives from our users who are aware of the Wordfence beta feed for scan signatures.

We do a more rigorous QA over the following hours and, once completed, the signatures proceed out into our production Premium feed so that our Premium customers receive this new detection capability in real-time. The important part is getting that protection to our users as quickly as possible before engaging in other research.

Going Deeper Down the Rabbit Hole

But now, of course, I was free to spend some time doing that research! As mentioned earlier, I had all of the information I needed to communicate with the attacker’s command and control server (C&C server). Rather than setting up a controlled infection and monitoring how the script runs, I can manually act as the “infected server” and see what other data I can gather by sending my own status updates.

The C&C server works via HTTP and includes several different endpoints. For the developers in the audience, it’s a REST-like API. When an infected server first executes, it encodes a set of values that give the attacker information about the operating system, hardware, and active processes and requests a configuration file.

I started by sending a false report for a non-existent server and I receive a customized configuration. What I receive is very similar to the JSON configuration file I examined earlier, with lower settings to match the lower quality machine I’m pretending to be, along with some other settings tailored to improve that machine’s specific performance during cryptomining. At this point the backdoor will wait quietly for several minutes so I did the same.

On the next report I sent the same machine information and a plausible change in the active processes and this time receive a set of commands. The C&C server instructed the backdoor to download a file, apply basic cloaking techniques, execute the file, and report the output of that file on the next instruction. I downloaded the file and it is another more recently compiled xmrig build. It also matches the different architecture I am claiming to have. The initial command is a test to confirm the program works correctly, and I simulated this and at the next report interval sent the expected data.

Finally the C&C server sent back an instruction set to run the miner, reconfigure the interval to send status reports, and to continue checking for a change of commands every 5 minutes. The goal of the attacker is to make money and this miner will use the server resources to mine Monero, a cryptocurrency which we have written about extensively in the past.

Monero is uniquely suited for this sort of hack for two reasons. Firstly, it is designed for individual anonymity and identifying the person who is receiving the mined coins is extremely difficult. Secondly, the mining algorithm is meant to be run on a CPU rather than GPU. Most web servers don’t have GPUs, and so mining a currency that allows you to effectively use a CPU is an ideal way to turn stolen web server processing power into hard cryptocurrency. When you aggregate a thousand or tens of thousands of hacked web servers together, that can result in a significant profit for an attacker.

Wrapping Up

Once I completed my analysis and ensured that Wordfence detects all variants of this new malware, I documented the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) of this new attacker along with logging the malware and other indicators of compromise (IOCs) into our internal threat intelligence platform.

It’s worth noting that the attacker who controls machines compromised by this infection is controlling a large cluster of stolen compute power. You can think of this as a private AWS cloud that the attacker can use for anything that needs computing resources. They are currently using their stolen cluster for cryptocurrency mining, but there is nothing preventing them from using these resources to conduct DDoS attacks, email spam campaigns, to brute force crack stolen password hashes or use the machines as proxies for misdirection while attacking other sites. They could even lease the compute resources to other attackers.

That is why I am excited whenever we have an opportunity to add detection for these kinds of new infections to the Wordfence malware scan. By analyzing a single compromised website and deploying detection to Wordfence, we have a good chance of shutting down this attacker once all sites running Wordfence detect this infection.

Closing Notes

I’d like to thank James for taking the time out of his busy schedule chasing malware to write this comprehensive post. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to post them in the comments below. Both James and I will be around to answer any questions. ~Mark Maunder

This post was written by James Yokobosky and edited by Mark Maunder with assistance from Dan Moen.

Comments

12:34 pm

How did this malware likely get installed on the victim's web server? I don't have WordPress running myself, so I can't make use of the benefits of Wordfence. Still, I'd love to learn how to protect my custom-coded web server.

1:16 pm

Hi Jesse,

As we mention in the post, we were given this site to clean after it had been infected for several months. Unfortunately the logs didn't exist for the time when the attack occurred, so we didn't have any forensic data that would allow us to determine the entry vector. So in this case we (sadly) had to settle for the forensic data without knowing how they got in, in the first place.

This really emphasizes the need for web access and error logs and retaining those logs. It helps us during incident investigations like this to determine how they gained entry and can help with attribution (who hacked your site).

Mark.

12:40 pm

Mark...this is a fascinating subject and I appreciate the details. First question...unanswered in the blog post...were you able to detect the hacker's location (country)? And, second, do you share your analysis with US and International cybersecurity authorities, both governmental and corporate? Thanks as always for the need-to-know information. Thanks to the WordFence team for their efforts.

1:13 pm

Hi James,

Occasionally when we see a pattern and we have attribution data we go on a hunt. Occasionally it results in something with a high degree of confidence:

https://www.wordfence.com/blog/2017/09/man-behind-plugin-spam-mason-soiza/

And occasionally we work with authorities, but we do so confidentially.

Regards,

Mark.

12:55 pm

Very interesting read, thanks for going into some detail about the methods/results.

1:15 pm

Thank you for this very informative article, it was a pleasure to read.

3:40 pm

Enjoyed the read, but have to admit that I'm still confused by what cryptocurrency mining actually is - I've read the Wordfence post that attempted to explain it (several times) but it seemed to zig mentally when I zagged. The downsides for the user whose host is running the malicious code are obvious, and the other potential uses for which the attacker can employ his access are also reason enough to continue all efforts to stamp this practice out.

My other question is: What degree of responsibility do the cryptocurrency providers have for the security of their currency when it comes to this sort of practice, and do you ever work directly with them? The approach described seems to be very hit-and-run and defensive and not proactive or systemic. If the cryptocurrency providers can detect abuses of their currency and block such transactions, that would attack the motivation behind these attacks. That seems an angle worth pursuing.

3:53 pm

Estimados James y Mark:

Ante todo, gracias por mantenernos informados.

He leído su artículo con atención, pero se me escapan muchas cosas de programación.

Mi pregunta es la siguiente:

¿Qué tendría que hacer para que ustedes analizasen mi web y saber que está libre de amenazas? Soy usuaria de Wordfence (no del paquete Premium). ¿Qué me recomiendan?

Muchas gracias de antemano.

Un cordial saludo,

Ana.

Translation:

Dear James and Mark:

First of all, thanks for keeping us informed.

I have read your article carefully, but I miss many programming things.

My question is this:

What would I have to do to make you analyze my website and know that it is free of threats? I'm a Wordfence user (not the Premium package). What dou you recommend?

Thank you very much in advance.

A cordial greeting,

Ana.

9:08 am

Thanks Ana. I recommend that you install Wordfence and run a scan. This will give you a thorough security check including scanning for malware and many other security problems.

Regards,

Mark.

Translation:

Gracias Ana. Recomiendo que instale Wordfence y ejecute un escaneo. Esto le proporcionará un completo control de seguridad, incluido el análisis de malware y muchos otros problemas de seguridad.

Saludos,

Marca.

5:36 pm

The lack of logging indicates the intruder likely stopped logging then deleted the old ones or truncated them to remove any trace of the infection events.

11:17 pm

Great work James! Love that kind of stuff, it's like you turn a rock and find a goldmine.

Keep rocking guys.

4:59 am

Fascinating to see how you go about this detective work to keep us safe. I love reading these kinds of forensic articles.

6:40 am

Quite interesting, thank you guys! For this detail well done anti hacking job and report, seems that sophistication has been present for a while.

Cheers!

9:50 pm

Thanks for the amazing job explaining this threat. It is interesting to see the sophistication described here. Given human nature when it comes to monetary gains, guess it is no surprise they went to such lengths!

Someone else in the comments asked about Wordfence reporting these actors to authorities. In a smiliar light, does Wordfence bring to the attention of the private cloud provider (the owner of the servers being hijacked as the command-and-control system for this hacker) that their cluster/servers have been compromised?

If I were ever in the position of having my server resources commandeered by someone else for whatever reason, I would appreciate hearing from a "Good Samaritan" about such a compromise. Is Wordfence our "Good Samaritan"?

Thanks!

10:37 am

Thanks for the post, very interesting reading.

I first installed WordFence several months ago after my host detected unusual traffic on my sites and kept blocking services.

For months I have been cleaning infected files and deleting malicious files. Changing passwords on all levels but it kept happening.

I believe the security problem to be at server level as it appears the attackers have root access. After months of expressing concerns to my host and receiving their canned response of you need to change passwords and contract a professional service I moved 2 of my domains to a new host and for 10 days they have stayed clean. This weekend I will move the remaining domains.

I suspect my sites have the same infection as I was contacted by primewp.com telling me my site was on a list of websites which were compromised with CrytoMining Malware (Cryptojacking). They offered a solution for $40 a month......not sure if they are legit or part of the group attacking my sites.

I have a collection of files that appear to be the source and can give you access to the infected host if it might be of use to the team in obtaining more info about this type of problem.

This situation cost me a great deal of time, stress and loss of business and I would like to assist in preventing this happening to other site owners out there.

If interested please contact me directly and I will give you access.

Thanks for the hard work, WF is a great tool to have available!!

11:29 am

Thanks Daniel. Sorry to hear you had to go through that.